I’m in the middle of a vocational transition. This essay explores what I’m learning about synchronicity, meaningful work, and building a practice that values depth over scale. Originally published on my Deer Path Substack.

I was washing dishes when I had to stop, pause my audiobook, and sit down. A tiny bird I’d never even heard of until a few days earlier — the jenny wren — was singing to me, delivering an important message that I didn’t want to miss.

For a few years, I’ve published a Substack newsletter about the history of people and places in Berkeley County, West Virginia. What began as a simple family tree on Ancestry.com ten years ago evolved into a passion.

For a long time, I regarded this as a cute little hobby, something to pass the time outside my real job as a professional journalist. But recently, I had an epiphany: This work isn’t frivolous. It’s a rich, ongoing historical research project. There’s a reason this work engrosses me so much, why it never tires or bores me. Why I remain devoted to it despite modest financial returns.

This work — to weave together interlocking stories of humble Appalachians in the insular Shenandoah Valley — nourishes my writer’s soul because it’s writing that means something, writing that endures beyond the 24-hour news cycle.

This realization seemed to arise out of nowhere on a recent afternoon, although I’m certain there was a long underground process — mycelial, invisible — that came before its fruiting.

I publish that newsletter every ten days, and my next publication date was two days away. I needed to choose from among the dozens of drafts I had squirreled away. I opened the folder on my Google Drive and randomly chose a story about The Lace Store, which I’d researched and written a year earlier.

The Lace Store was a Martinsburg, West Virginia, institution for several decades of the 1900s. The business started out selling only lace — hence the name — but expanded so much over the years that it became like a small-town Walmart where families went to buy coats, train sets, school textbooks and more.

The “hook” of my story was a man named Billy Clohan, who’d started out as a clerk in the store after high school, but took over managing the whole place after its owner died suddenly in his 50s. When I published the article, it represented a shift. It was the first of my newsletter’s 228 articles in which I presented the work for what it’s always been: enduring historical research.

The same afternoon that the Lace Store newsletter hit my subscribers’ inboxes, I was washing dishes while listening to an audiobook. As my soapy cloth passed over forks and plates, I encountered a passage about an elderly woman who’d abandoned her house decades earlier in rural Kentucky. The narrator visited that old house and noticed a jenny wren had built a nest on a shelf in the shed.

Jenny wren.

That’s when I turned off the tap and pressed pause on the audiobook.

In the Lace Store article, one small detail I’d included was that seventy years ago, the store manager had built a house near his place of business so he could walk to work. The home where he and family lived was on Jenny Wren Drive.

I didn’t immediately understand why, but I knew this synchronicity was significant.

A sign to keep going

For decades, I treated synchronicities as instructions: signs showing me which way to go, messages telling me what to do next.

But lately, I’m realizing synchronicities are confirmations. They show up after I’ve already decided, saying: Yes, keep going.

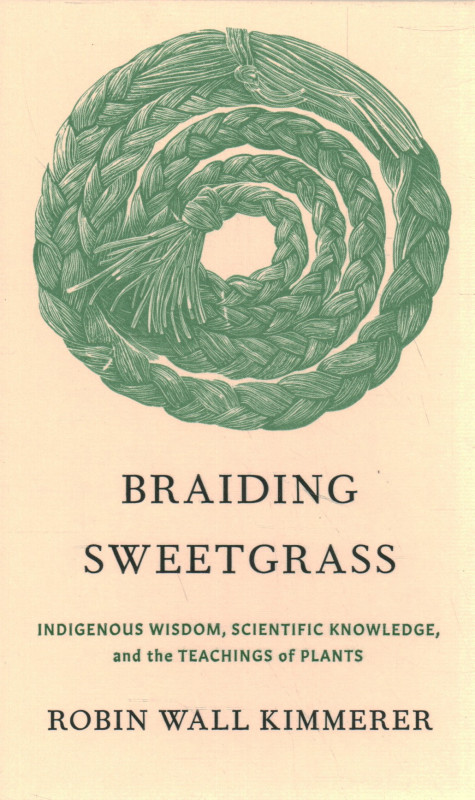

The audiobook I was listening to that day was Braiding Sweetgrass. The memoir by botanist Robin Wall Kimmerer is a meditation on indigenous wisdom and plant ecology. Throughout the book, she braids together three strands: scientific knowledge from her botany training, traditional ecological knowledge from her Potawatomi heritage, and personal narrative. The book asks: What if we saw plants not as objects, but as teachers? What if we approached the land with reciprocity instead of extraction? She documents how indigenous practices — often dismissed as primitive — contain sophisticated ecological wisdom that science only later began to understand.

It fascinated me that I had chosen this 12-year-old book to read now, and that it told me a story about a jenny wren on the same day a jenny wren appeared in my newly published history article — the first one of over two hundred articles that I presented with the gravitas it deserved.

No wonder Kimmerer had stepped in to be an ideal mentor for me at this crossroads.

Two months after losing my journalism job, instead of plunging into a LinkedIn search, I’m thoughtfully planting seeds for my future work. Kimmerer does exactly what I’m learning to do: bridge institutional credentials with sacred wisdom and story.

For years, I eked out a subsistence in the corporate media world by churning out viral stories, newsletters geared toward high open rates, and an assembly line of social media posts engineered to game the algorithm.

The factory-worker model of digital news production had never been my career dream, but I adapted to it as the news business changed. In fact, I performed it brilliantly. As someone who grew up in poverty and instability, who was homeless for part of my childhood, there was part of me that believed I had to keep frantically producing for survival. When I finally asked my managers, “I’d like to do work that feels more meaningful,” they had no interest. There was no room for it.

The mass layoff this past fall of nearly the entire editorial staff of my former employer is what finally freed me from the factory production line.

Now, as I’m going through all my old clips to build my portfolio, the viral headlines I once produced make me laugh, and sometimes cringe. Ephemeral and silly stories. Two alligators fighting on someone’s front porch. A hot cop who jumps in a river to save a woman. The top 10 coolest weapons in U.S. military history. A woman named Crystal who’s busted for crystal meth. And the headline that got me invited onto someone’s podcast: Five guys arrested over fistfight at Five Guys.

Beneath all this clickbait, like a heart of pine floor that’s revealed when flimsy vinyl laminate is peeled away, lies my real writing. These are the articles I wrote when I had the chance to slow down, choose topics that meant something, get a feel for my subjects. To take the time to notice textures and details, a tone of voice, the way the light hit. To reflect on what one small story says about the larger human condition.

For years, I was enmeshed in the metrics-obsessed dictates of the modern newsroom. It was only after my layoff — after I was freed from the frantic 24/7 news cycle — that I was able to slow down enough to remember.

A strong foundation

My calling is and has always been to write at the thresholds, to witness at the edges, where important stories are held quietly, waiting for someone attentive enough to notice them.

I just so happened to start reading Braiding Sweetgrass around the same time I started understanding this.

In the chapter where the jenny wren shows up, Kimmerer documents an elderly woman (Hazel) whose life reflects the history of a place. The author visits an abandoned house to witness the evidence of its past life. In the nest, she sees physical evidence of life continuing in forgotten places. She preserves memory before it disappears.

This is exactly what I’m called to do.The jenny wren nests in overlooked places. A nest is a home built from scraps. A shelter constructed in a tight space, made from materials others might overlook. A safe place for new life. My true writing weaves facts and words together to build metaphorical nests, creating protective containers for overlooked stories.

Billy Clohan’s store started out selling only lace. It’s an old-fashioned thing to do. Lace is an intricate and patient craft, made from threads woven together. A feminine technology with patterns nearly invisible unless you look closely. An intricate structure requiring small but precise work.

Similarly, the jenny wren weaves nests from scraps. She inhabits domestic edges: hedges around houses. Stone walls near homes. Sheds behind houses.

That’s where my work lives, too: Kitchen table oral histories. Small-town newspaper archives. Tiny old churches that no longer fit into gentrified neighborhoods. The hospital chaplain who grabs a TropiGrill sandwich in between comforting families on the worst day of their lives. A forgotten spring hiding behind a tall condo building. The underestimated secretary whose vision and creativity outshines the high-paid executives she reports to. A veteran who served honorably and is navigating re-entry into everyday civilian life. Disappeared stores on quiet streets.

I’m weaving a vocation that’s precise and patient, that requires being a good listener and observer. I’m called to honor the lives of regular people. I preserve what would otherwise be lost.

The jenny wren appeared twice in one day with the same message: You’re on the right path. Keep going. Build your nest from what you have. Sing clearly from the edges.

The jenny wren doesn’t need to be large to have a clear voice.

Neither do I.

About my work

If you’re looking for a writer who approaches storytelling as stewardship rather than extraction, you learn more about my work here or contact me below.

Leave a comment