This is the origin story of my work as a legacy curator. It started with a question at an aunt’s kitchen table and grew into a vocation I didn’t know I was building.

It started the way these things often do: with a question I couldn’t answer.

I was sitting at an aunt’s kitchen table when she mentioned a name I’d never heard before. Someone’s second wife. A child who died young. A move to another state that no one talked about. The details were vague, the timeline unclear, and within minutes the conversation had moved on to something else entirely.

But the question stayed with me: Who were these people? What happened to them?

I began to take an interest in my family tree. It started simply, on Ancestry.com. The software makes it easy to flesh out names, dates, and the basic scaffolding of who belonged to whom. Census records led to marriage licenses, which led to property deeds, which led to newspaper obituaries, which led to — more questions. Every answer I found opened three new mysteries.

And I loved every minute of it.

Ten years later, I’m still following those threads. Somewhere along the way, what began as casual curiosity became something else entirely: a vocation that weaves together everything I love: research, writing, history, the pleasure of studying old newspaper clippings and century-old documents, the detective work of piecing together fragmented lives.

This is the work I was made to do. I just didn’t know it yet.

How Curiosity Became Methodology

The research I do for my Berkeley County, West Virginia, ancestry project uses the same methodology I bring to legacy and oral history work with living clients:

Archival research across fragmented sources. Whether I’m piecing together a 19th-century family through census records or organizing decades of a client’s accumulated materials, the process is identical: trace the thread, note the gaps, synthesize fragments into coherent narrative.

Pattern recognition. I notice, for example, that a man named Billy Clohan lost his father at five, then spent 45 years preserving what his employer built — a lifetime of stewardship rooted in early loss. I notice that three generations of women in a family all married at 15, revealing economic constraint more than romantic choice. These aren’t just family stories. They’re windows into how people survive, what they protect, what they pass down.

Ethical curation. Not everything belongs in the public record. I make the same judgment calls with historical figures that I make with living clients: What serves the story? What honors the person? What protects descendants while preserving truth?

Narrative synthesis. Raw data means nothing without interpretation. A census entry listing a 12-year-old as “domestic servant” becomes the story of a girl with a dead mother and no options. A property deed from 1940 becomes evidence of a man buying his mentor’s business and relocating it when he couldn’t secure the original building. This is what I do: translate records into meaning.

What Draws Me to the Archives

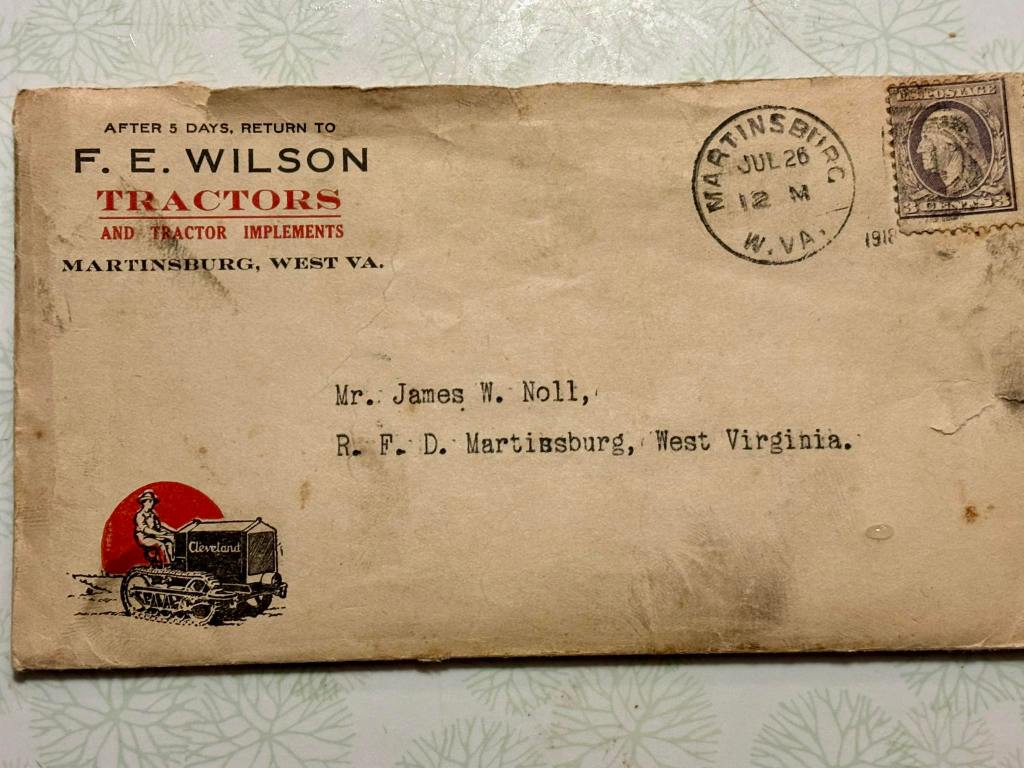

There’s something about studying a document from 1887, the handwriting looping and faded, that grounds me in a way nothing else does. These aren’t abstractions. These are records of actual moments: a marriage witnessed and signed, a piece of land changing hands, a death recorded in careful script.

I love the detective work. The thrill when a name I’ve been searching for suddenly appears in an unexpected place. The satisfaction of finding the missing piece that makes the whole puzzle snap into focus. The challenge of conflicting sources, such as three different documents giving three different birth years, and having to figure out which one is most likely accurate, and why.

I love immersing myself in a specific time and place. Reading newspaper accounts of the local impact of a devastating flu epidemic. Studying the 1870 census to understand who lived where, who owned property, who worked as laborers or servants. Tracing migration patterns as families left Appalachia for Ohio factories or western homesteads.

But what keeps me coming back isn’t just the research itself. It’s the stories that emerge from the fragments.

When the Research Becomes Story

A census entry doesn’t just list a name and age. It tells you that a 12-year-old girl is listed as “domestic servant” in someone else’s household while her mother is nowhere to be found. That’s not data. That’s a child with a dead or absent mother and no options.

A property deed doesn’t just record a transaction. It shows you that a family farm sold in 1893 for far less than its value, suggesting economic desperation or death or migration under pressure.

A marriage record doesn’t just note a union. It reveals a 15-year-old bride and a 42-year-old groom, which tells you something about gender, economics, and the limited choices available to young women without property or male protection.

This is where the work becomes something more than genealogy. I’m not just collecting names and dates. I’m reconstructing lives. I’m finding the human story in the bureaucratic record.

And somewhere in that process, I realized: This is the exact skill set I am passionate about doing with me legacy work with living clients.

How Ancestry Research Became Professional Practice

The research I do for my West Virginia ancestry project uses the exact methodology I bring to legacy and oral history work with living clients.

Most of my journalism career was measured in 24-hour news cycles. Write it, publish it, move on. The work seemed to evaporate as soon as it was published. There was rarely time to go deep, to sit with complexity, or to follow a thread just to see where it led.

Ancestry research operates on a different timeline. I’m documenting lives that ended decades or centuries ago for readers who won’t be born for decades or centuries to come. The woman I’m researching has been dead for 120 years. The story I’m writing might not matter to anyone for another 50.

This is the rhythm that feels right to me: not immediate impact, but enduring preservation. Not just performance for today’s audience, but also stewardship for future understanding. Not the frantic churn of daily news, but the patient work of making sure what mattered doesn’t disappear.

When I’m immersed in the archives, time moves differently. My breathing slows. Hours pass without me noticing. I’m in the zone.

What the Dead Teach Me About the Living

When I research Billy Clohan running the Lace Store for 45 years after his boss died, I’m learning what institutional stewardship looks like. When I trace a woman who lost her mother at two weeks old and raised her own daughters alone after her husband died young, I’m learning about resilience across generations. When I document a Scottish immigrant who worked coal mines then became a prominent farmer and horticultural society president, I’m learning about reinvention.

These aren’t just their stories. They’re templates for understanding how people navigate loss, build institutions, preserve what matters, pass down what endures.

This is what I bring to client work: a deep familiarity with the patterns of human survival and the long arc of legacy.

The Same Question at Different Scales

Whether I’m researching a 19th-century family or helping a living client organize their life’s work, I’m asking the same questions:

- What’s the story that holds this together?

- What pattern keeps repeating?

- What got preserved and what disappeared — and why?

- What do future people need to understand about this life or this work?

- How do I honor complexity without creating chaos?

The answers look different at different scales, but the questions are identical.

Why I Publish the Ancestry Work

I could do this research privately and never share it. But making it public serves multiple purposes:

It builds audience. People interested in Berkeley County history, Appalachian genealogy, or well-researched family narratives find my work. Some of them eventually become clients.

It demonstrates methodology. Anyone can read my work and see exactly how I research, what sources I use, how I synthesize information, what I do when records conflict or disappear. This is portfolio evidence of skills that transfer directly to client work:

- Synthesizing archival research + institutional history + community memory into coherent narrative

- Handling multiple voices without losing the thread

- Crediting sources appropriately (historical societies, individual contributors, primary documents)

- Turning informal memories, even social media comments, into legitimate historical evidence

- Balancing factual precision with emotional resonance

It shows voice. Clients can see how I handle sensitive material, how I write about ordinary lives with respect and precision, how I balance emotional resonance with factual accuracy.

It proves commitment to the long view. I’m not chasing clicks or virality. I’m building a body of work that will matter to someone, someday, even if I never meet them.

The Work Is the Same

At the end of the day, whether I’m researching a store that closed in 1969 or helping a client document their 40-year career, I’m doing the same thing: finding the narrative that holds fragmented material together, preserving what might otherwise be lost, creating a record that future people — family, researchers, historians — can build on.

The dead strangers I research are practice and proof. They teach me the work. And they show clients what I can do when handed fragments and asked to find the story.

I publish ancestry research on my “They Lived in Berkeley County” Substack newsletter. If you’re interested in legacy documentation or oral history services for your family or organization, contact me below.

Leave a comment