About this research and writing project:

The challenge: The 2001 tech bust displaced thousands of workers, but most coverage focused on stock prices and executive decisions rather than what happened to the people who lost their jobs. When 263 Cirent Semiconductor employees were laid off in Orlando, their union negotiated an unusual severance provision: $5,000 per worker for retraining. Twenty of them chose bartending school, creating an unexpected collision of two worlds.

My approach: I embedded in a weeklong bartending course at ABC Bartending School, sitting alongside former clean-room technicians as they memorized 140 drink recipes instead of microchip specs. I captured the jarring contrasts (sterile suits and safety glasses versus smoke-filled bars and blonde jokes, precision machinery versus counting ounces by eye) and traced how workers processed sudden displacement through dark humor and collective grief. The piece required balancing the absurdity of the situation with genuine respect for people navigating economic upheaval, and showing how retraining programs actually function on the ground versus in policy documents.

The impact: Published in the Orlando Sentinel during the height of the dot-com crash, the story humanized tech-sector layoffs by showing what happens after the press release. It documented a specific moment in labor history when blue-collar tech workers had to improvise survival strategies, and revealed how people maintain dignity and community even when their industry collapses.

Originally published in the Orlando Sentinel on May 2, 2001

Two Tuesdays after he lost his job, James Gordon sat at a dark bar. On the other side of dusty miniblinds, behind vodka and rum bottles, lunchtime traffic wheezed along Mills Avenue.

Gordon hunched over, writing intently.

- Martini: 1/2 oz dry vermouth, 1 1/2 oz gin or vodka, olive

- Dry vodka martini: 1/4 oz dry vermouth, 1 3/4 oz vodka, olive

- Extra dry martini: couple of drops dry vermouth, 2 oz gin or vodka, olive

Down the length of a letter-sized sheet of paper bound into a spiral notebook, Gordon jotted recipes.

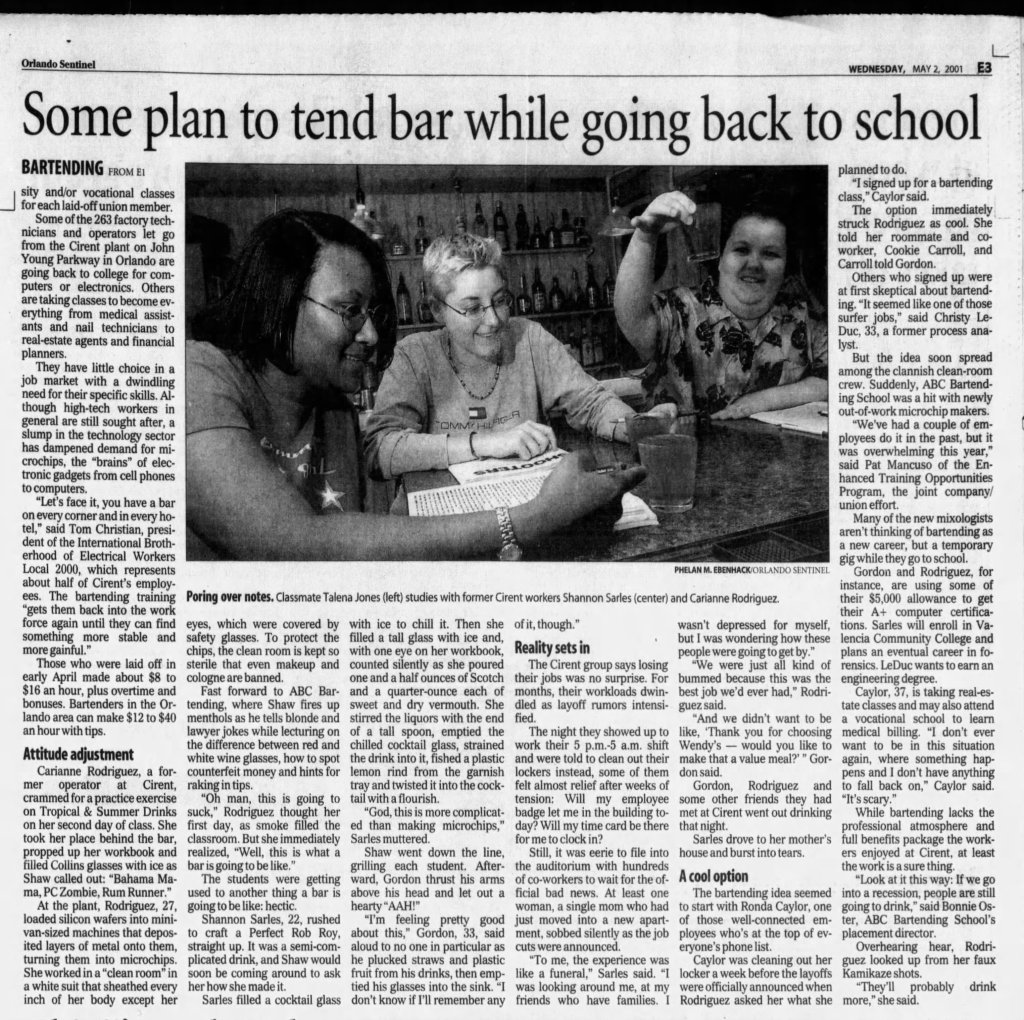

A few minutes later, Noel Shaw entered the room, stubbed out his cigarette in a plastic ashtray and boomed in his Bronx accent, “OK, how you all doin’?”

Gordon and the dozen others lined up at the bar at Orlando’s ABC Bartending School would soon find out — Shaw, the school’s teacher and director, graded their tests in about 30 seconds each. Gordon did well: another 100-percent score. He was mastering the 140 drinks taught in the weeklong course, remembering little things, such as what creme de cassis tastes like (currants) and which drink gets a sugared rim (a sidecar).

He and 20 others laid off from Cirent Semiconductor in early April have enrolled in the bartending school, hoping to make a living slinging margaritas instead of microchips. Through a unique arrangement, Cirent and their labor union are picking up the $495 tab for each.

Their classroom — 20 steps above Mills, past a lobby with peeling wallpaper and a ratty sofa — boasts all the comforts of a hometown tavern: neon beer signs, a radio tuned to soft rock and an icemaker that crackles like a popcorn machine.

In fact, you wouldn’t know it wasn’t a real bar until you took your first sip: All the drinks here are made with colored water. There’s no liquor, no beer, no orange juice, no cream in the place. A White Russian comes out looking like dirty dishwater.

Other students in a recent session of the class included a laid-off dot-com worker, a former marketing executive, and a car saleswoman and an air-traffic controller both seeking part-time jobs.

But former Cirent workers made up a solid half of the roster on this recent week. They were taking advantage of part of their severance package — an agreement between Cirent and the International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers that pays for up to $5,000 in university and/or vocational classes for each laid-off union member.

Some of the 263 factory technicians and operators let go from the Cirent plant on John Young Parkway in Orlando are going back to college for computers or electronics. Others are taking classes to become everything from medical assistants and nail technicians to real-estate agents and financial planners.

They have little choice in a job market with a dwindling need for their specific skills. Although high-tech workers in general are still sought after, a slump in the technology sector has dampened demand for microchips, the “brains” of electronic gadgets from cell phones to computers.

“Let’s face it, you have a bar on every corner and in every hotel,” said Tom Christian, president of the International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers Local 2000, which represents about half of Cirent’s employees. The bartending training “gets them back into the work force again until they can find something more stable and more gainful.”

Those who were laid off in early April made about $8 to $16 an hour, plus overtime and bonuses. Bartenders in the Orlando area can make $12 to $40 an hour with tips.

ATTITUDE ADJUSTMENT

Carianne Rodriguez, a former operator at Cirent, crammed for a practice exercise on Tropical & Summer Drinks on her second day of class. She took her place behind the bar, propped up her workbook and filled Collins glasses with ice as Shaw called out: “Bahama Mama, PC Zombie, Rum Runner.”

At the plant, Rodriguez, 27, loaded silicon wafers into minivan-sized machines that deposited layers of metal onto them, turning them into microchips. She worked in a “clean room” in a white suit that sheathed every inch of her body except her eyes, which were covered by safety glasses. To protect the chips, the clean room is kept so sterile that even makeup and cologne are banned.

Fast forward to ABC Bartending, where Shaw fires up menthols as he tells blonde and lawyer jokes while lecturing on the difference between red and white wine glasses, how to spot counterfeit money and hints for raking in tips.

“Oh man, this is going to suck,” Rodriguez thought her first day, as smoke filled the classroom. But she immediately realized, “Well, this is what a bar is going to be like.”

The students were getting used to another thing a bar is going to be like: hectic.

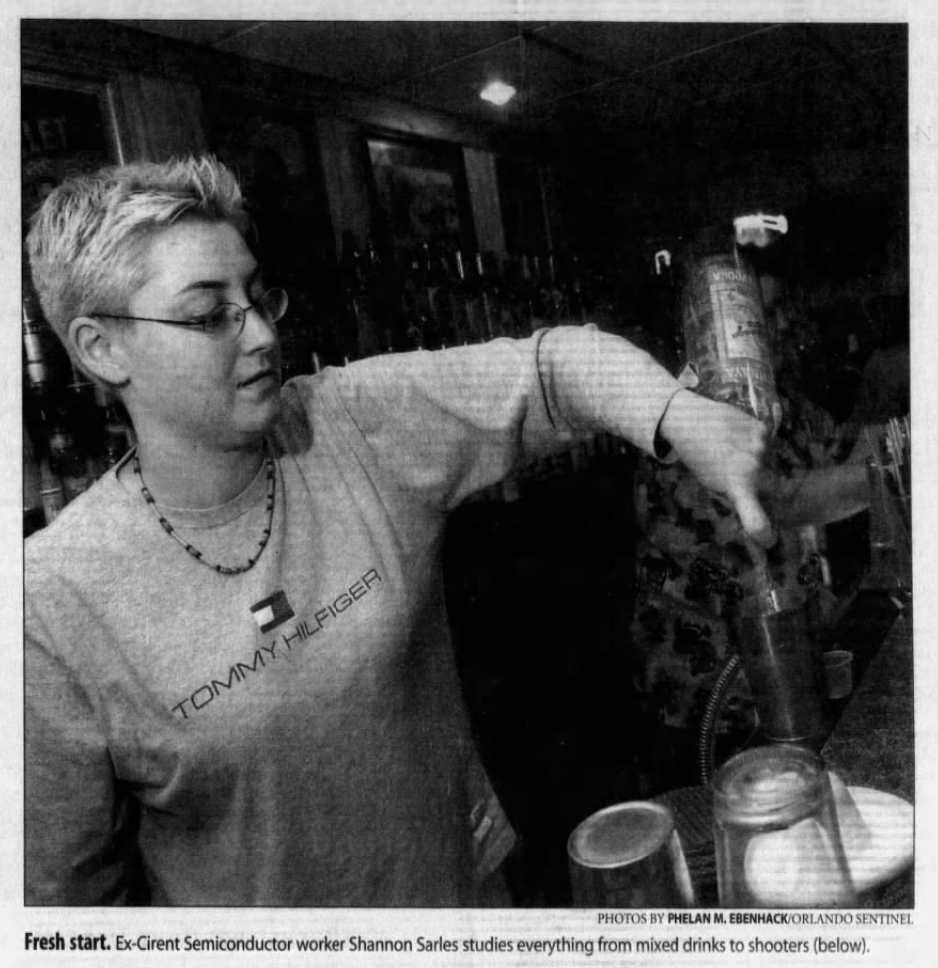

Shannon Sarles, 22, rushed to craft a Perfect Rob Roy, straight up. It was a semi-complicated drink, and Shaw would soon be coming around to ask her how she made it.

Sarles filled a cocktail glass with ice to chill it. Then she filled a tall glass with ice and, with one eye on her workbook, counted silently as she poured one and a half ounces of Scotch and a quarter-ounce each of sweet and dry vermouth. She stirred the liquors with the end of a tall spoon, emptied the chilled cocktail glass, strained the drink into it, fished a plastic lemon rind from the garnish tray and twisted it into the cocktail with a flourish.

“God, this is more complicated than making microchips,” Sarles muttered.

Shaw went down the line, grilling each student. Afterward, Gordon thrust his arms above his head and let out a hearty “AAH!”

“I’m feeling pretty good about this,” Gordon, 33, said aloud to no one in particular as he plucked straws and plastic fruit from his drinks, then emptied his glasses into the sink. “I don’t know if I’ll remember any of it, though.”

REALITY SETS IN

The Cirent group says losing their jobs was no surprise. For months, their workloads dwindled as layoff rumors intensified.

The night they showed up to work their 5 p.m.-5 a.m. shift and were told to clean out their lockers instead, some of them felt almost relief after weeks of tension: Will my employee badge let me in the building today? Will my time card be there for me to clock in?

Still, it was eerie to file into the auditorium with hundreds of co-workers to wait for the official bad news. At least one woman, a single mom who had just moved into a new apartment, sobbed silently as the job cuts were announced.

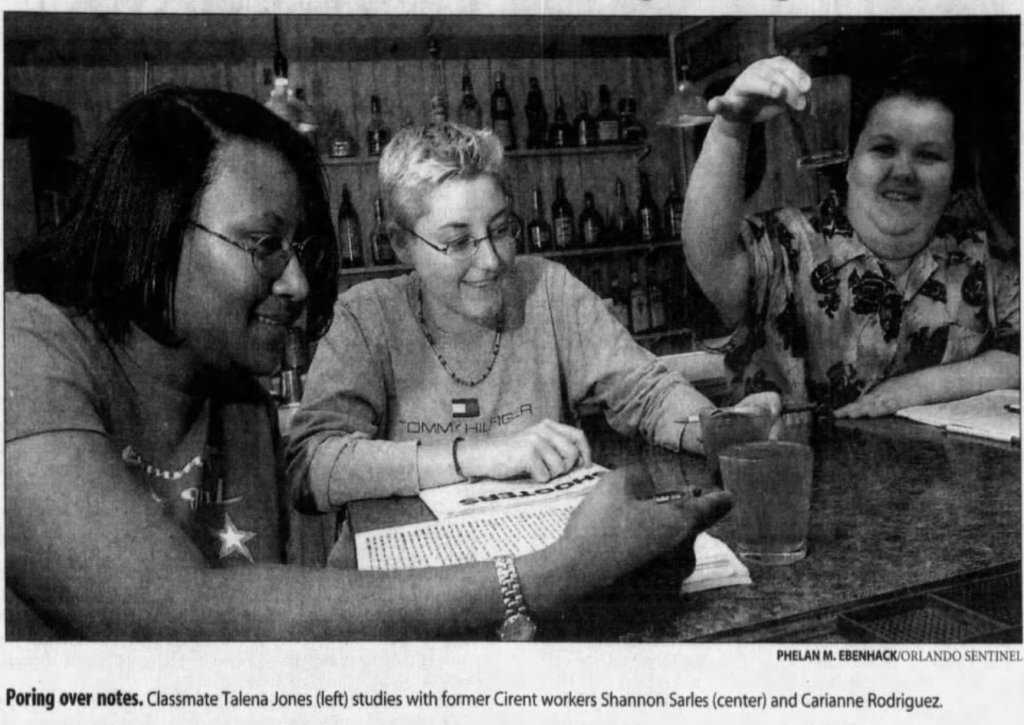

“To me, the experience was like a funeral,” Sarles said. “I was looking around me, at my friends who have families. I wasn’t depressed for myself, but I was wondering how these people were going to get by.”

“We were just all kind of bummed because this was the best job we’d ever had,” Rodriguez said.

“And we didn’t want to be like, `Thank you for choosing Wendy’s — would you like to make that a value meal?’ ” Gordon said.

Gordon, Rodriguez and some other friends they had met at Cirent went out drinking that night.

Sarles drove to her mother’s house and burst into tears.

A COOL OPTION

The bartending idea seemed to start with Ronda Caylor, one of those well-connected employees who’s at the top of everyone’s phone list.

Caylor was cleaning out her locker a week before the layoffs were officially announced when Rodriguez asked her what she planned to do.

“I signed up for a bartending class,” Caylor said.

The option immediately struck Rodriguez as cool. She told her roommate and co-worker, Cookie Carroll, and Carroll told Gordon.

Others who signed up were at first skeptical about bartending. “It seemed like one of those surfer jobs,” said Christy LeDuc, 33, a former process analyst.

But the idea soon spread among the clannish clean-room crew. Suddenly, ABC Bartending School was a hit with newly out-of-work microchip makers.

“We’ve had a couple of employees do it in the past, but it was overwhelming this year,” said Pat Mancuso of the Enhanced Training Opportunities Program, the joint company/union effort.

Many of the new mixologists aren’t thinking of bartending as a new career, but a temporary gig while they go to school.

Gordon and Rodriguez, for instance, are using some of their $5,000 allowance to get their A+ computer certifications. Sarles will enroll in Valencia Community College and plans an eventual career in forensics. LeDuc wants to earn an engineering degree.

Caylor, 37, is taking real-estate classes and may also attend a vocational school to learn medical billing. “I don’t ever want to be in this situation again, where something happens and I don’t have anything to fall back on,” Caylor said. “It’s scary.”

While bartending lacks the professional atmosphere and full benefits package the workers enjoyed at Cirent, at least the work is a sure thing.

“Look at it this way: If we go into a recession, people are still going to drink,” said Bonnie Oster, ABC Bartending School’s placement director.

Overhearing her, Rodriguez looked up from her faux Kamikaze shots.

“They’ll probably drink more,” she said.

Read this article on OrlandoSentinel.com

Leave a comment