About this research and writing project:

The challenge: Infrastructure projects are typically covered at the moment of controversy and then forgotten once construction is complete. By 2022, State Road 417 had become invisible infrastructure — just another commuter route — but the tradeoffs made decades earlier (140 acres of destroyed wetlands, a bridge that “amputated” Lake Jesup from cleaner river currents, neighborhoods transformed by proximity to multi-lane highways) had never been revisited or measured against initial promises.

My approach: I traced the 35-year arc of the Seminole Expressway from initial opposition in 1987 through its 1994 opening to its current role in Central Florida’s highway network. Using archival Sentinel reporting, I reconstructed specific resident concerns (the Winter Springs homeowner facing a highway 150 feet from his house, the Oviedo property owner worried about lost investment) and tracked what actually happened to those properties. I documented environmental predictions (oil pollutants, wetland destruction, lake degradation) against current conditions, revealing that Lake Jesup is now “one of the sickest in Florida” despite a $1.2 million restoration project. The piece required synthesizing decades of coverage, property records, environmental data, and agency transitions to show the full cost of infrastructure “progress.”

The impact: Published in the Orlando Sentinel, the article provided historical accountability for development decisions, showing readers what Central Florida gained (airport access, shorter commutes) and what it permanently lost (wild shorelines, functioning wetlands, a healthy lake ecosystem). It demonstrated that community opposition, even when vocal and organized, made no difference once the route was approved.

Originally published in the Orlando Sentinel on March 4, 2022

In the late 1980s, “confused and angry” Seminole County property owners showed up at expressway authority meetings to oppose plans for a new highway cutting through their neighborhoods.

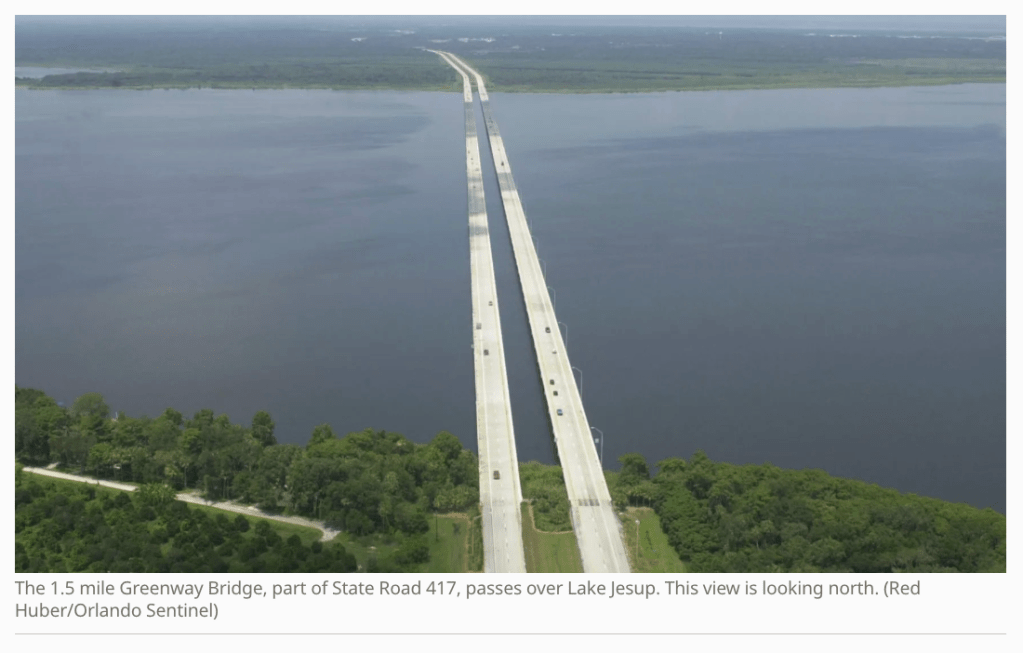

Today, the Seminole Expressway section of State Road 417 begins at Interstate 4 in Sanford, curves east of Lake Mary, and crosses Lake Jesup before winding its way south through Oviedo.

When the highway was still in the planning stages, it was Central Florida’s most significant road-building project since I-4 opened in 1965.

On this day 35 years ago, on March 4, 1987, an article inside the local section of The Orlando Sentinel quoted several property owners who peppered Seminole County Expressway Authority officials with questions.

The first part of State Road 417 opened that same year, but a key Seminole County segment would not be completed until 1994.

Before construction began in Seminole, many residents were worried a highway would hamper quality of life in their neighborhoods as well as value in their real estate investments.

A Winter Springs homeowner complained that one proposed route “would be 150 feet from my house,” a leafy bedroom community that now abuts the Cross Seminole Trail.

The toll road is now 1.3 miles east of that home.

Another homeowner, in Oviedo, lamented “I’ll never get my money back.” The article described LaVerne Lynch’s property, off Bear Gully Creek, as a “$200,000 house.”

The multi-lane highway is now a mere 1,300 feet from that home’s front door. But its market value today is nearly half a million dollars, according to a Realtor.com estimate.

Home values weren’t the only worry. There were major environmental concerns as well.

Cecilia Height, chair of the of the Sierra Club of Central Florida, called the planned bridge over Lake Jesup “disgraceful.”

Many local residents shared her opinion, heartbroken at the thought of further degradation to the alligator-filled Jesup, with its wild shoreline and large floodplain.

Officials acknowledged that the road “would harm or destroy 140 acres of wetlands and release oil pollutants from the bridge onto the lake,” according to a 1992 Sentinel article.

The compromise: a $1.2 million wetlands restoration project on the lake’s north shore.

Despite the Lake Jesup Conservation Area, the lake is one of the sickest in Florida, and road-building “amputated Jesup from the cleaner currents of the St. Johns River,” the Sentinel’s Kevin Spear wrote in 2018.

In the end, the outcry made no difference. A route was approved, and in May 1994, a 6-mile segment of the Seminole Expressway from S.R. 434 to U.S. 17/92 in Sanford opened.

In exchange for a more polluted environment and paved-over acreage, the county gained easier access to downtown Orlando, the theme parks and Orlando International Airport.

S.R. 417’s half-circle beltway is now 55 miles long and stretches down to Osceola County.

The Orange County section is called the Central Florida GreeneWay, named after Jim Greene, the late chairman of the Orlando-Orange County Expressway Authority.

Florida’s Turnpike Enterprise, created in 2002, now oversees the parts of the road that are in Seminole and Osceola counties.

Leave a comment