About this research and writing project:

The challenge: The 2003 Columbia disaster is remembered as a sudden tragedy, but warning signs stretched back decades to the shuttle’s very first days at Kennedy Space Center. In 1979, workers had to glue 7,000 heat-shield tiles onto the brand-new orbiter before it could fly, foreshadowing the thermal protection failures that would kill seven astronauts 24 years later. This continuity between early design problems and catastrophic failure had been lost in coverage that treated the disaster as unthinkable rather than as the culmination of known, unresolved issues.

My approach: I traced Columbia’s troubled history from its 1979 arrival at KSC (when front-page Sentinel Star coverage documented extensive repair work on a craft fresh from the assembly plant) through its 22-year operational life to the February 2003 disaster. Using archival newspaper coverage and former Sentinel space editor Michael Cabbage’s investigative book, I connected the persistent tile and foam problems that plagued the shuttle from the beginning to the foam strike that breached the wing during launch. The piece required holding two timelines simultaneously (the excitement of 1979 versus the devastation of 2003) and documenting institutional failure (NASA’s rejection of Pentagon spy camera imagery, the known foam problem allowed to continue) without sensationalizing the deaths of seven astronauts.

The impact: Published in the Orlando Sentinel, the article reframed the Columbia tragedy from unforeseeable accident to predictable outcome of unresolved technical and cultural problems. It provided historical context showing that the “most complex machine in the world” was compromised from its first arrival in Florida, challenging narratives that treated the disaster as shocking rather than symptomatic.

Published in the Orlando Sentinel on March 26, 2022

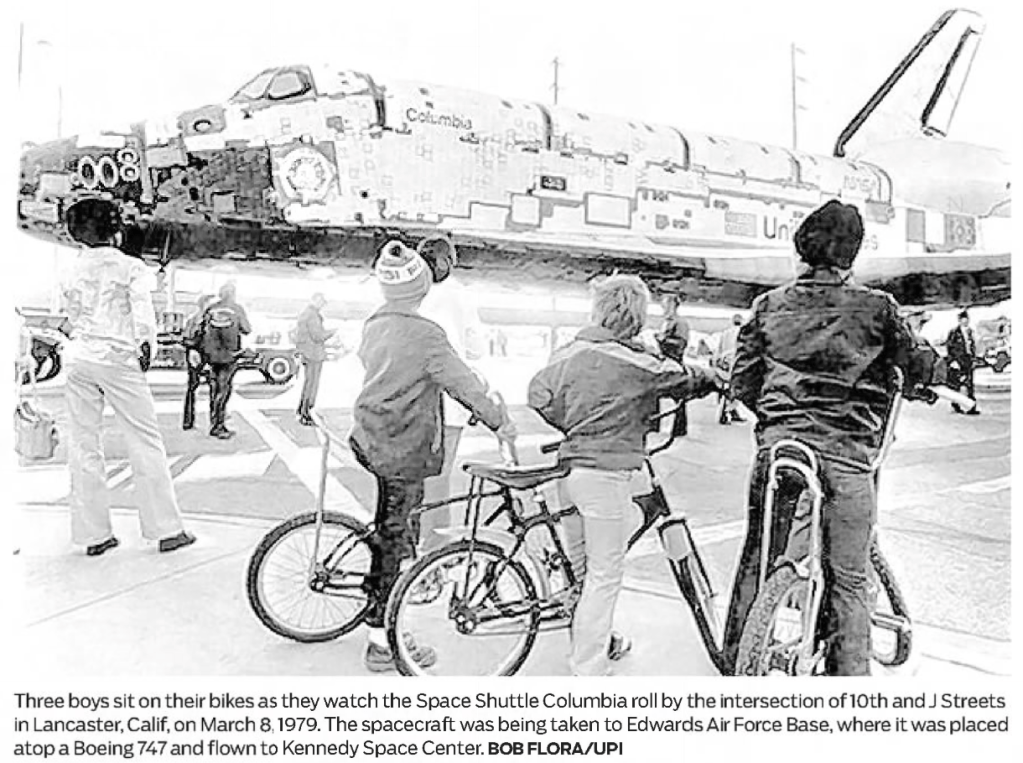

Twenty-four years before Space Shuttle Columbia disintegrated during its return to Earth killing all seven astronauts on board, the Sentinel Star wrote about the repair work the brand-new orbiter already needed just days after it rolled off the assembly plant.

In March 1979, workers at Kennedy Space Center had to begin gluing 7,000 heat-shield tiles onto Columbia’s surface after its arrival from California to Florida.

The expensive tiles, part of the technology that allows a craft to be re-used, have long been a headache for the space shuttle program.

On March 26, 1979, the story about the patch work the Columbia needed in Florida ran at the top of the front page of the Sentinel Star newspaper. The craft had arrived at Kennedy Space Center a day earlier, on March 25, 1979.

But the cause of the February 2003 Columbia disaster was a hole in the orbiter’s left wing, which was hit by a large piece of foam that had broken off its external tank seconds after liftoff 16 days earlier.

The damaged wing held up fine in space, but could not withstand the searing heat of re-entry.

“This problem with foam had been known for years, and NASA came under intense scrutiny in Congress and in the media for allowing the situation to continue,” according to Space.com.

‘Unthinkable’ tragedy

The Columbia tragedy is often described as “unthinkable.” Many people, even some within NASA, considered launch to be the most dangerous aspect of a space mission, especially after the Challenger disaster 17 years earlier.

Early in the morning of Feb. 1, 2003, a photographer who got up before dawn to capture Columbia’s path over California noticed with alarm a “big red flare come from underneath the shuttle,” according to the 2008 book “Comm Check…: The Final Flight of Shuttle Columbia” by former Orlando Sentinel space editor Michael Cabbage and William Harwood.

The spaceship was hurtling uncontrollably toward Earth at thousands of miles per hour.

When it broke apart on its way to Kennedy Space Center, its debris was scattered across hundreds of miles in Texas, Louisiana and Arkansas.

The KSC Visitor Complex displays some pieces of the recovered remains.

But most of the nearly 84,000 remnants are in storage in KSC’s Vehicle Assembly Building and aren’t open to the public.

The most complex machine in the world

In the shuttle’s beginnings, on March 26, 1979, the story about the patch work the Columbia needed in Florida ran at the top of the front page of the Sentinel Star newspaper.

The craft had arrived at Kennedy Space Center a day earlier, on March 25, 1979.

KSC crew were excited about the brand-new vehicle — at the time, the most complex machine in the world other than the human bodies it was to carry.

But they were also exhausted by the sheer amount of work that fell to them.

After four years of construction in California amid myriad technical delays, Columbia still needed not only months of tile-gluing work, but it was also left to workers here to install its three main engines.

The tragedy nearly a quarter-century later devastated the space program and the nation.

Columbia, after its maiden flight in April 1981 — the first shuttle to reach space — was in operation for 22 years and 28 missions.

The Columbia mission astronauts who were killed were Rick Husband, commander; William C. McCool, pilot; Michael P. Anderson, payload commander/mission specialist 3; mission specialists David M. Brown, Kalpana Chawla and Laurel Clark; and Ilan Ramon, payload specialist 1.

“Comm Check” explores problems with NASA culture, such as how the agency had rejected an offer by the Pentagon to use spy cameras to capture images of Columbia’s breached wing in orbit.

“NASA’s best and brightest … failed to recognize the signs of an impending disaster,” according to the book’s promotional summary.

Read this article on OrlandoSentinel.com

Leave a comment