About this research and writing project:

The challenge: Civil rights milestones are often sanitized in retrospect, losing the specific texture of resistance and risk that made them significant. The 1955 interracial Little League game in Orlando (the first known integrated game in the South) had faded from public memory despite its historical importance, and the elderly players who lived through it were aging out. Without documentation, the full story of white managers resigning in fury, Black children traveling 400 miles knowing the dangers of lynching, and city officials scrambling hours before game time to decide whether to allow it would be lost entirely.

My approach: I reconstructed the event through archival Sentinel coverage, Chris Lamb’s investigative book “Stolen Dreams,” and a 2018 documentary, and the monument unveiling where surviving players gathered. I contrasted the realities of white boys’ carefree childhoods with Black boys facing slurs, curfews and violence, then documented the institutional resistance (managers quitting, white teams forfeiting rather than play, city recreation administrators citing segregation policy) that nearly prevented the game. The piece required navigating the dignity of elderly Black players who endured gas station bathroom refusals and crowd hostility while capturing the unexpected warmth of 750 spectators applauding when they took the field. I preserved specific details (the team saying the Lord’s Prayer before leaving the bus, the injured pitcher’s bad day, the final 5-0 score) that keep the story grounded in lived experience rather than abstract triumph.

The Impact: Published in the Orlando Sentinel, the article documented a forgotten civil rights moment before the last living witnesses were gone, providing context for the Barrier Breakers monument and challenging sanitized narratives about integration. It showed that progress wasn’t inevitable or welcomed but fought for by children who “just wanted to play the ballgame” while adults raged around them.

Originally published in the Orlando Sentinel on March 25, 2022

In the 1950s, baseball was America’s game.

Boys were as obsessed with the sport then as they are with video games now, collecting cards by the hundreds and tracking their favorite Major League players.

In the small town of Orlando, kids played in orange groves before developers had trees razed for houses. A group of boys in the College Park neighborhood then gathered for games at Princeton Park, a rectangle of green space ringed by oak trees.

When they weren’t playing ball, they rode their bikes as far as their legs would take them, their mothers having no idea where they were.

Happy, peaceful, carefree. This was the reality of many white boys in middle-class, midcentury South.

Black boys enjoyed far less peace and freedom. They grew up being threatened by whites, called n——, forced to stay in “their” part of town, either barred from certain businesses or made to use “colored” entrances, and had Black-only curfews imposed on them by city officials.

But Black boys loved baseball, too. They idolized heroes like Jackie Robinson and Willie Mays. They gathered for free-wheeling sandlot games in their neighborhoods and had their own Little League teams.

It was against this backdrop that two groups of these boys from different worlds came together in a historic moment in Orlando in August 1955.

For the Little League State Championship, the Pensacola Jaycees, an all-Black Little League team, took on the all-white Orlando Kiwanis on their home turf at Optimist Park next to Lake Lorna Doone.

It was the first known integrated Little League game in the South, and it almost didn’t happen.

On Thursday, nearly 67 years after the milestone, now-elderly players from the Pensacola Jaycees and Orlando Kiwanis teams came together again at Lake Lorna Doone Park for a rainy ceremony to unveil a monument commemorating the historic event.

The bronze structure, called Barrier Breakers, depicts two 12-year-old boys, one from each team, wearing their uniforms and caps and holding a bat and ball.

The Edward E. Haddock Jr. Family Foundation commissioned the piece, which is the final work by artist and former NFL football player George Nock, who died in November.

Nock was a member of the 1966 Morgan State University football team, which won the Tangerine Bowl in Orlando, becoming the first historically Black college team to win an integrated bowl game.

Orlando Mayor Buddy Dyer presided over Thursday’s event, along with District 5 City Commissioner Regina I. Hill, and Haddock foundation Executive Director Ted Haddock.

Racism creates barriers

Racism creates barriersNearly seven decades ago, many racist Southern whites were enraged by the idea of Black and white kids playing together on the same field.

Jackie Robinson had broken the Major League color barrier in 1945. And the Supreme Court ruled school segregation unconstitutional in 1954. But segregation persisted in countless sectors of public and private life, including children’s games.

When Orlando approved the interracial match-up for the 1955 championship, one of the Orlando Kiwanis Little League managers resigned in a fury.

“If you are a Southerner, live like a Southerner,” Kiwanis co-manager Dwight DeVane declared. “I have to go by my beliefs, live with them the rest of my life.”

The other Kiwanis manager, Mel Rivenbark, whose son was a player, wasn’t much happier but stayed on.

“I don’t like the idea of playing the game, personally. But I feel I owe it to the boys,” he said, according to Stolen Dreams: The 1955 Cannon Street All-Stars and Little League Baseball’s Civil War, by Chris Lamb, scheduled for publication in April.

The players themselves didn’t care.

“We just wanted to play the ballgame; that’s what it meant to us,” Stewart Hall, the Kiwanis team captain, later said.

The Pensacola Jaycees were overjoyed to learn they’d been selected as Little League All-Stars.

The adults in charge of the white teams in their district had refused to play against them, and wanted to exclude the Black teams altogether, but Little League ruled against them. The white teams’ refusal to play was designated a forfeit.

The Jaycees were therefore declared the district champions, with the next step the state contest in Orlando. They began the 400-mile journey to Orange County, an area rampant with violent racism that was only a generation removed from the Ocoee massacre and was, at the time, the sixth-deadliest county in America for lynchings.

Along the way, they had to use the side of the road for a bathroom, since gas stations took their fuel money but refused to allow them to use the restrooms.

The boys knew the dangers of leaving their segregated neighborhoods. They knew about lynchings across the South — 14-year-old Emmett Till would be brutally murdered in Mississippi three weeks later. Still, for many of the young baseball players, some of whom had never left Pensacola, the trip was the highlight of their lives.

White Orlando leaders spar

Literally as the Jaycees were en route, city officials in Orlando were still scrambling to determine whether the “Negro” team would be allowed to take part in the tournament.

“City Recreation Administrator Tom Starling said this morning he knew at least three of the white teams would ‘pack up and go home’ if the Negro youngsters were allowed to compete,” the Orlando Evening Star reported on August 8, 1955, the eve of the game.

Starling maintained that “it is a city policy not to allow athletic play between Negroes and whites.”

However, Mayor J. Rolfe Davis believed the decision wasn’t a city matter, but up to Little League officials.

The Orlando City Council ultimately agreed with Davis. Keep us out of it, they essentially said. It’s a Little League decision.

The ruling was such big news that it ran at the top of A-1 of the Orlando Sentinel on August 9, 1955, the day of the game.

Hours before the scheduled start time, crowds began streaming into Optimist Park next to Lake Lorna Doone.

Most Little League games were lucky to draw 50 spectators. But at least 750 people showed up to watch on this day. The bleachers couldn’t hold them all. It was standing room only down both sides of the field, and crowds were packed three and four deep by the fences.

The Jaycees had butterflies in their stomachs. They were a long way from home, and they weren’t sure how they would be treated in Orlando.

When they showed up at the field, however, they were met with applause.

“The Orlando players remembered watching the Pensacola team exit their bus and walk to the baseball field,” Lamb wrote in Stolen Dreams. “The team came off the bus in single file and walked to the dugout, and then they got in a circle and said the Lord’s Prayer.”

As the game got underway, the Jaycees heard clapping and cheers for their plays, but also received some boos and hissing. It made them nervous.

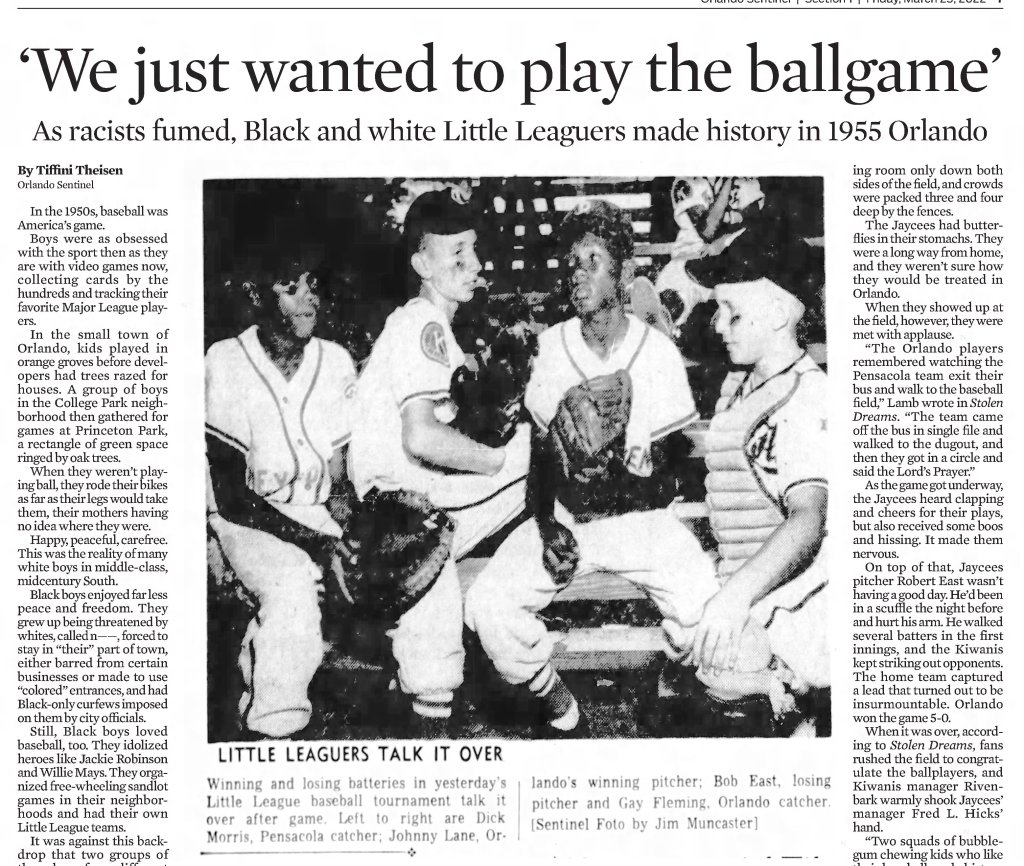

On top of that, Jaycees pitcher Bob East wasn’t having a good day. He’d been in a scuffle the night before and hurt his arm. He walked several batters in the first innings, and the Kiwanis kept striking out opponents. The home team captured a lead that turned out to be insurmountable. Orlando won the game 5-0.

When it was over, according to Stolen Dreams, fans rushed the field to congratulate the ballplayers, and Kiwanis manager Rivenbark warmly shook Jaycees manager Fred L. Hicks’ hand.

“Two squads of bubblegum chewing kids who like their baseball made history here yesterday,” the Orlando Sentinel printed on the front page the next day.

Information from “Long Time Coming: A 1955 Baseball Story,” a 2018 documentary about the Jaycees-Kiwanis game and its players, was used to compile this report.

View this article on OrlandoSentinel.com

Leave a comment